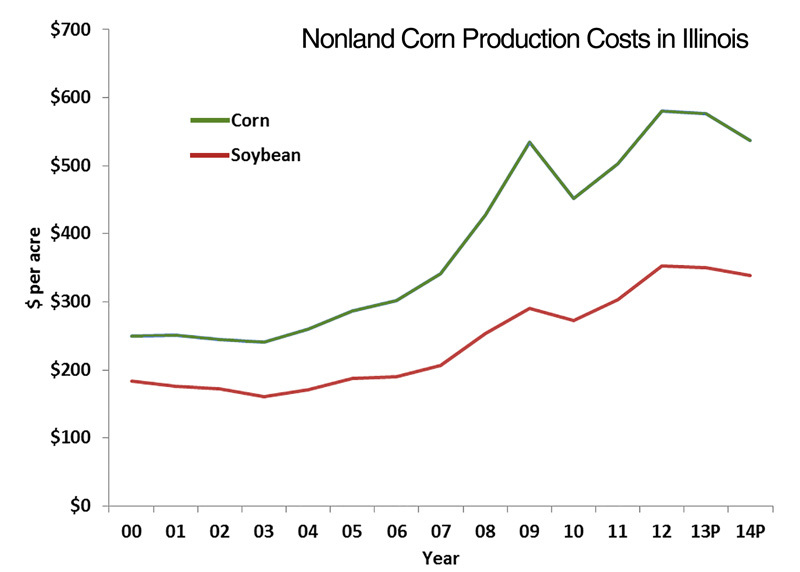

Production Price Up

PHOTO: JOHN DEERE & COMPANY

February 14, 2014

BY Chris Hanson

Advertisement

Advertisement

Related Stories

A pan-European road trip featuring cars and trucks powered by renewable fuels logged 77,500 kilometers across 16 countries in a real-world demonstration that these fuels deliver significant GHG reductions.

Scientists at ORNL have developed a first-ever method of detecting ribonucleic acid, or RNA, inside plant cells using a technique that results in a visible fluorescent signal. The technology could help develop hardier bioenergy and food crops.

International Air Transport Association has announced the release of the Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF) Matchmaker platform, to facilitate SAF procurement between airlines and SAF producers by matching requests for SAF supply with offers.

ATR and French SAF aggregator ATOBA Energy on June 19 signed a memorandum of understanding (MOU) to explore ways to facilitate and accelerate sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) adoption for ATR operators.

The USGC has added Sarah McLeeson as its new trade policy coordinator. McLeeson will organize staff and member travel, make arrangements for visiting trade teams and facilitate program planning and execution.